What is psychological wellbeing? Why might it matter in sport?

We are seeing a rising awareness of mental health and wellbeing concerns in current and retired high performance athletes. Sport organizations and governments are also recognizing that a duty of care towards the athletes that represent our nation is imperative. But, what does it mean for athletes to be psychologically well? And how can we foster this wellbeing throughout and beyond athletic careers?

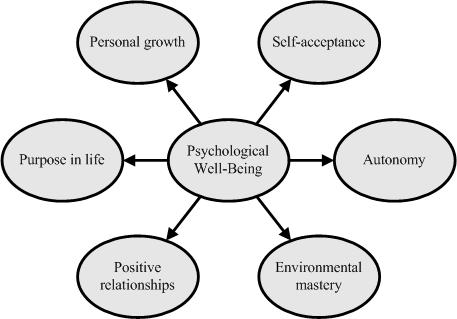

There are two types of wellbeing that people experience. One type focuses on feeling well, and is called hedonic wellbeing. It is when people experience high levels of positive affect (in order words, feeling positive!), and a high degree of life satisfaction. Another type of wellbeing focuses on functioning well and is termed eudaimonic wellbeing. It refers to living well and actualizing one’s potential, and focuses on cultivating a higher degree of purpose and meaning in life. It is this type of wellbeing, psychological wellbeing, that we are looking to foster in elite athletes, given its long-term association with quality of life.

(Ryff, 1989)

To learn more about research attending to what psychological wellbeing might mean, look, and feel like for athletes, you may find the resources below to be of interest:

When and how might athlete wellbeing be challenged?

It is not uncommon for athletes to struggle with psychological wellbeing. Elite athletes are faced with multiple stressors throughout their athletic careers that have the potential to constrain their abilities to remain well. For example, the Covid-19 pandemic created social conditions where isolation, lockdowns, and harms to human health led to cancelling of training and competitions, and notably the postponement of the Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games. This created uncertainty in the lives of many athletes. Athletes also commonly face injuries, difficulties in relationships with coaches, sport organizations, and teammates, performance plateaus, body image concerns, and financial instability, which have been known to engender psychological stress and distress.

Mental health and sports in the media

Given the harrowing nature of these experiences, athletes have started to speak out about their experiences with psychological distress and mental health concerns. In particular, various documentaries and podcasts have explored experiences of mental health in sports, and athletes have also been featured in media stories. Examples can be found below.

To learn more about research pertaining to how athletes experience injury, retirement, coach struggles, performance plateaus, and how these might compromise and lead to challenges to wellbeing, the following research studies may be of interest:

How can athlete wellbeing be supported?

One question that our research team has been interested in answering is – what can be done to support and foster athlete psychological wellbeing? This would presumably include creating conditions where athletes can experience autonomy, self-acceptance, positive relations, environmental mastery, purpose in life, and personal growth. If these conditions were in place, we know that athletes would be in a better position to reap the physical, social and psychological benefits that come from participating in sport. They would also be in a better position to navigate the many challenges to their particular pressures from coaches, parents, and fans, experiences with athletic transitions, injuries, and poor performance, for example.

To learn more about how athletes can be supported to thrive, please see the following papers:

How are athletes differentially situated to experience wellbeing?

Our research team, including Erica Bennett, Andrea Bundon, Peter Crocker, and Lisa Trainor has been conducting a series of interviews with athletes over the last 3 years to learn about their experiences of wellbeing. Findings from this work have revealed that ableism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, and racism are experienced by many athletes. These findings are unsurprising given the systems of power in place within sport that privilege some athletes over others. However, they are very troubling. This discrimination and marginalization faced by women, disabled, queer, trans, nonbinary, and racialized athletes has often negatively impacted their autonomy, relationships with others, training and performance, and overall health and wellbeing. The onus has been unduly placed on these athletes to protect their own wellbeing, and has created harm and compromised their abilities to strive for and achieve their full potential. Athletes have shared with us that they have often been forced to advocate for themselves and for their communities in order to protect their wellbeing and to thrive despite and in spite of working within an inequitable sport system. This advocacy has brought them purpose and meaning in life, yet also stress and distress.

Our hope is that by learning more about how athletes who are diverse in social location experience wellbeing, sport sector stakeholders such as coaches, sport organization staff, sport psychologists, mental skills consultants, and athletes themselves, will be able to learn how they can continue to work towards creating a more equitable sport system where all athletes are welcomed and supported.

To learn more about how athletes might be differentially situated to protect their wellbeing, see the following paper and presentations attending to athletes’ experiences of inequities in relation to the postponement of the Tokyo Games:

What’s Next?: (De)Constructing Elite Athletes’ Psychological Well-being?

Psychological well-being is a significant topic in the world of sport as an increasing number of elite athletes have come forward in the media expressing well-being related challenges. Currently, leading definitions of psychological wellbeing such as Ryff’s six dimensions (1989) as well as the general positing that one is psychologically well when they are living well and actualizing their potential (Deci & Ryan, 2008) captures ‘global’ psychological wellbeing. However, these definitions of psychological wellbeing do not take context into account (e.g., sport). Context is important as judgements of psychological wellbeing are related to personally significant contextual domains (Diener et al., 2003). Important questions remain, therefore, as there is no conclusive evidence determining the configuration of (sport-specific) athlete PWB (Lundqvist & Sandin, 2014).

To address the context-specific nature of psychological wellbeing, PhD candidate Lisa Trainor is currently exploring Olympic and Paralympic athletes’ perceptions of the configuration of athlete psychological wellbeing. She interviewed 28 athletes (7 Paralympic; 19 Olympic) from four countries (Canada; United Kingdom; Australia; New Zealand) at two time points, as well as asked athletes to bring photographs that represented high and low moments of their psychological wellbeing in sport. From this research on the identification of contextually significant domains of athlete psychological wellbeing, resources and guidelines will be developed to inform the sport sector and sport organizations at the local, national, and international level regarding what is needed to support athlete wellbeing.

References

Ryff, C.D. 1989. “Happiness is Everything, or is It? Explorations on the Meaning of Psychological Well-Being.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069–1081. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069 .

Digital Museum Credits

Contributors: Dr. Erica Bennett, University of British Columbia; Dr. Andrea Bundon, University of British Columbia; Dr. Peter Crocker, University of British Columbia; Lisa Trainor, University of British Columbia

Corresponding author: Dr. Erica Bennett, University of British Columbia, erica.bennett@ubc.ca